THE SISTER TOWERS

On Dispossession and Citymaking

Global urbanisation and post-industrial capitalism has created an ever-expanding class divide; rapid economic growth pushes the working class further from city centres, and into what many refer to as a “planet of slums” (Davis, 2006), whilst property developers accumulate capital and continue to re-invest and shape our city.

When these capitalist relations of production and accumulation transform urban space through geographically concentrated production surplus, the overworked and precariously housed workers are driven from their neighbourhoods. The homes of the city’s “disposable citizens” (Nixon, 2018); rich with history and community, are demolished to make way for expensive private property investments. Gentrification, though often re-branded as urban-redevelopment, has no consideration for the needs and lives of these vulnerable, largely black, indigenous and migrant families. Friedrich Engels observed this dynamic occurring in Germany’s industrial centres in 1872:

“The breeding places of disease, the infamous holes and cellars in which the capitalist mode of production confines our workers night after night, are not abolished; they are merely shifted elsewhere! The same economic necessity that produced them in the first place, produces them in the next place.”

(Engels, 1872)

(Engels, 1872)

The simultaneous exploitation of our planet for building materials to feed this insatiable desire for continual demolition and reconstruction is an enduring and irreversible threat to the natural world and our everyday lives. These violent and destructive processes remain at the heart of capitalist urbanism - architects must rethink the perceived essentiality of demolition in the city and instead look to improve and add to what already exists.

Social geographers such as Elliot-Cooper, Hubbard and Lees describe displacement as “an intensely-felt and experiential process of un-homing” (Elliot-Cooper, Hubbard and Lees, 2019). The loss of one’s home permeates deeper than just physical relocation; the scope of the emotional and material displacement produces “geographies of wounding” (Philo, 2005) through space and time - one’s body, household, street, neighbourhood, city, past memories, difficult present and the foreboding future.

Social housing initiatives provide a layer of protection for those who face the continual threat of negative gearing and rising rent. However, this vital source of housing is no exception to the threat of the privatisation of land for profit. In this case, the residents of Waterloo Estate continue to face damaging media coverage and ongoing development proposals regarding the future of their community and livelihoods due its close and profitable proximity from the CBD. With this in mind, our intervention aims to engage deeply with the rich community that calls Waterloo home. We must draw upon and improve spaces and connections of value, to enhance and sustain the integral things that already exist. And this must be done without un-homing or demolition; a sustainable intervention that responds to both increased population density and the lives of the current residents.

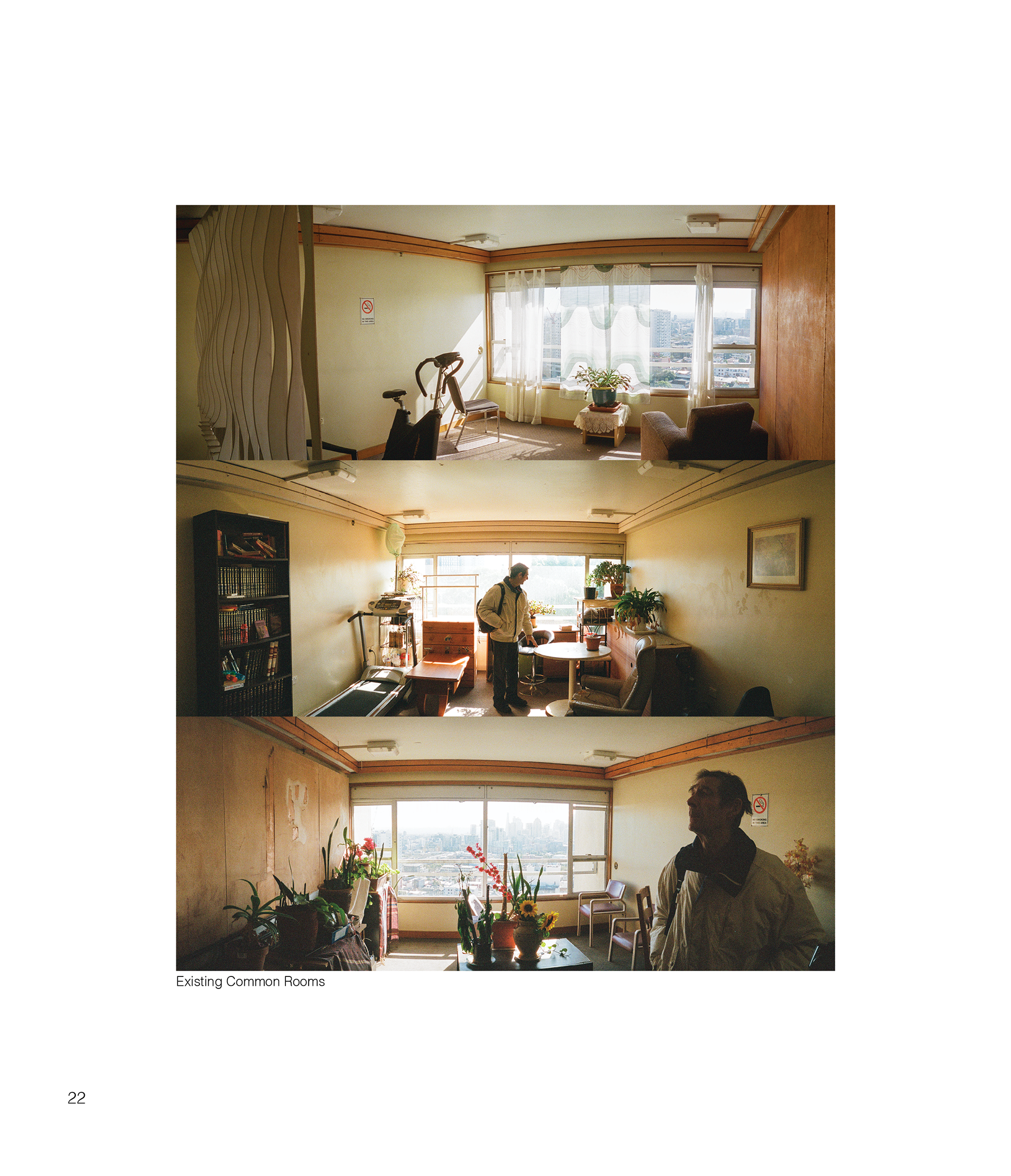

We took a people-based approach to observing and analysing the existing site. We were guided through the estate by residents and members of the Waterloo Public Housing Action Group; a tour characterised by stories and sentimentality, but also anger and hopelessness towards the future of the community. We were taken through the towers, and quickly noticed that the internal typology of the common room was vital for the social lives of the largely elderly residents. These spaces are crucial to many in these towers, especially for those lacking mobility, and would not have many outside interactions. As many of these tenants rarely leave their units, a vertical village is already taking place; with each floor serving almost as a street within the larger tower neighbourhood.

The towers have 27 common rooms each - 29 including the ground floor common room and observatory room on the roof which are currently closed. As a by-product of Covid and the ongoing complacency of redevelopment in the near future, these common areas and rooms are slowly but surely being reduced one by one.

Situated on the Northern facade, these common rooms have prime position - beautiful sunlight and access to the city by way of unobstructed views. And vice versa, the recognizable face of these towers from the city is defined by the common. These spaces uniquely are decorated and furnished differently based on who lives on the floors, and provided the backdrop for many personal stories which we heard.

Situated on the Northern facade, these common rooms have prime position - beautiful sunlight and access to the city by way of unobstructed views. And vice versa, the recognizable face of these towers from the city is defined by the common. These spaces uniquely are decorated and furnished differently based on who lives on the floors, and provided the backdrop for many personal stories which we heard.

Through these discussions, we understood what people loved about living there, the community, and how existing architecture shapes how this is formed. Our approach was clear - to focus on these communal spaces; to improve the lives of residents through expanding and allowing them to serve to their full potential. And then to use this way of thinking whilst we increase density.

As a result of our investigations, our solution was to improve existing, add density and hero the common room. The new buildings are carefully placed in order to maximise Northern light and frame the view between the existing towers whilst playfully interacting with the form and locations. The location of the sister towers have minimal impact or overshadowing apartments in the surrounding buildings. Site constraints lead us to frame Turanga tower, as there was more leniency in regards to free space on the ground plane and shadows.

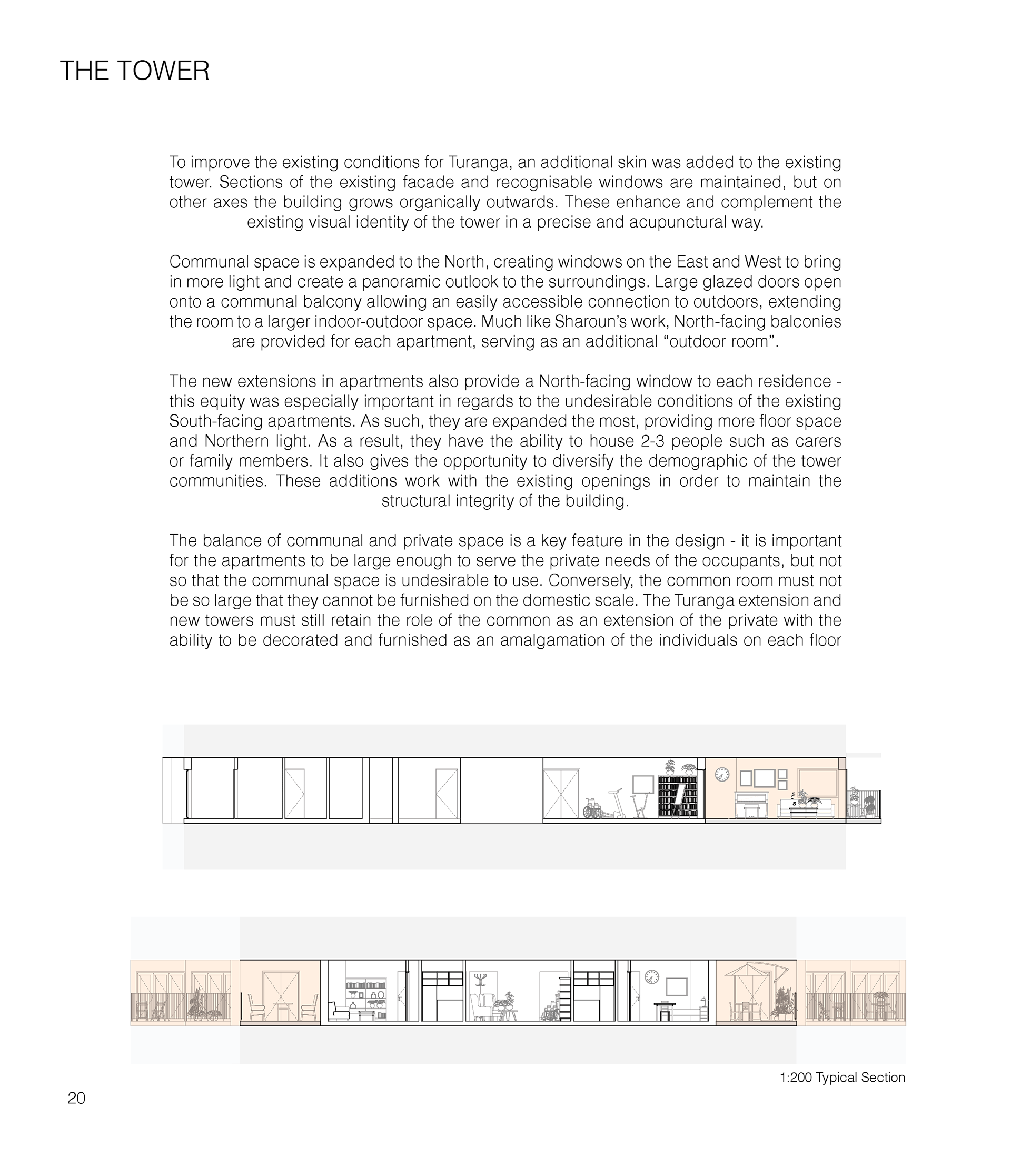

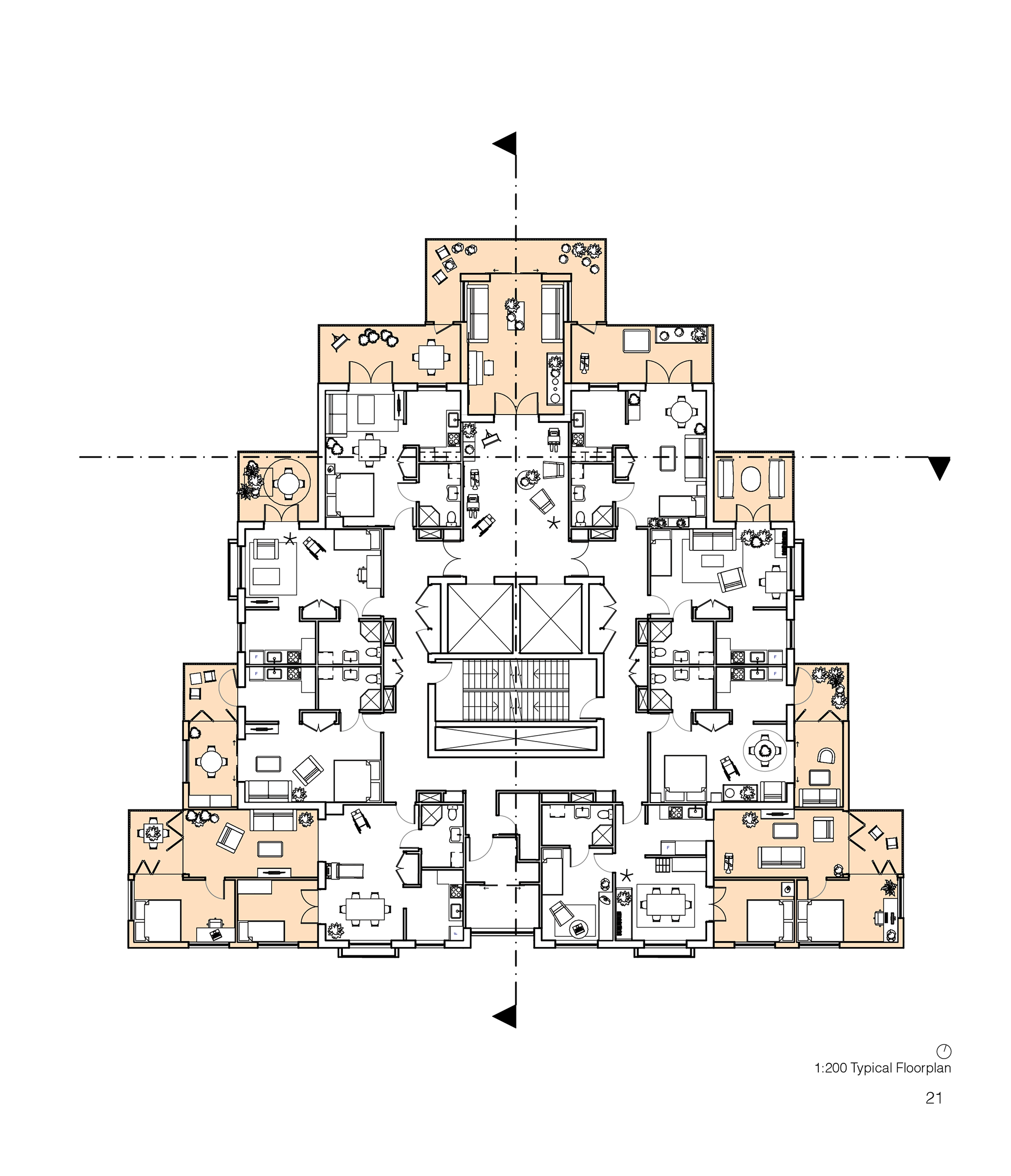

To improve the existing conditions for Turanga, an additional skin was added to the existing tower. Sections of the existing facade and recognisable windows are maintained, but on other axes the building grows organically outwards. These enhance and complement the existing visual identity of the tower in a precise and acupunctural way.

Communal space is expanded to the North, creating windows on the East and West to bring in more light and create a panoramic outlook to the surroundings. Large glazed doors open onto a communal balcony allowing an easily accessible connection to outdoors, extending the room to a larger indoor-outdoor space. Much like Sharoun’s work, North-facing balconies are provided for each apartment, serving as an additional “outdoor room”.

The new extensions in apartments also provide a North-facing window to each residence - this equity was especially important in regards to the undesirable conditions of the existing South-facing apartments. As such, they are expanded the most, providing more floor space and Northern light. As a result, they have the ability to house 2-3 people such as carers or family members. It also gives the opportunity to diversify the demographic of the tower communities. These additions work with the existing openings in order to maintain the structural integrity of the building.

The balance of communal and private space is a key feature in the design - it is important for the apartments to be large enough to serve the private needs of the occupants, but not so that the communal space is undesirable to use. Conversely, the common room must not be so large that they cannot be furnished on the domestic scale. The Turanga extension and new towers must still retain the role of the common as an extension of the private with the ability to be decorated and furnished as an amalgamation of the individuals on each floor neighbourhood.

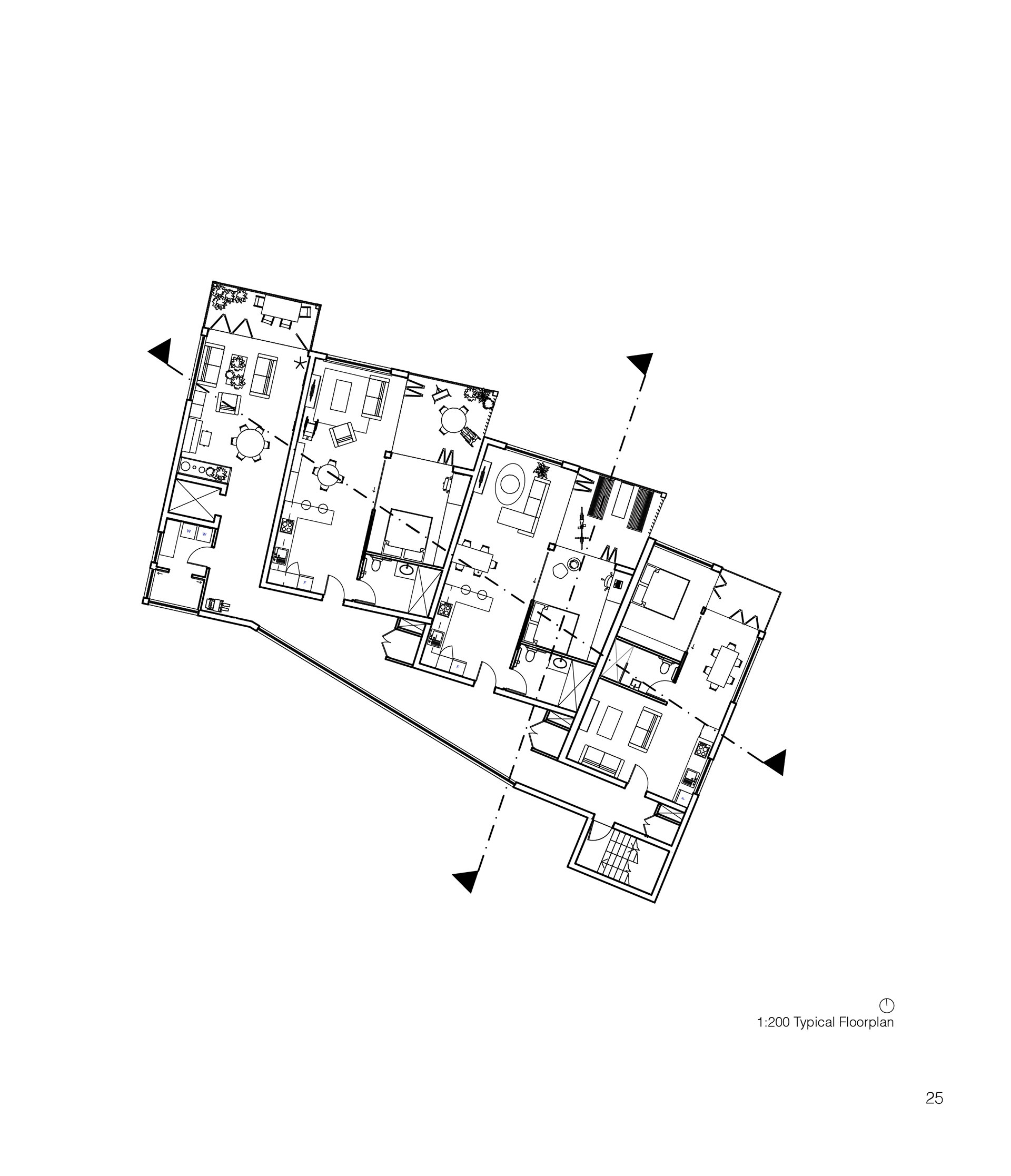

The additional sister towers are contemporary in their form - they exist to compliment, but not copy - with a significantly lighter frame and considered operable openings. Taking inspiration from the Juliet building, the new towers have units that fan outwards at different angles towards the sun, maximising thermal and lighting capability whilst maintaining visual privacy. Similarly, the unit plans are L-shaped allowing for each balcony to have an entrance from the bedroom and living space. These outdoor rooms are protected from the Western side, and on the East have operable vertical louvres to adjust for privacy and sunlight where necessary. The bedroom space sits adjacent to the living space - gaining air and light. It can be closed off or opened by sliding partitions which when hidden within the internal bathroom wall, leave almost no trace apart from a column - a small spatial demarcation of existing living space into one more personal.

A circulation spine exists on the South side - the stepped shape also allows for additional storage space directly outside the unit, this is more accessible than the traditional basement storage spaces which is especially useful for the elderly. The communal space receives sunlight from the North and West, and works similarly to that of the existing towers - left unprogrammed to serve the unique needs of each floor, blurred indoor and outdoor space, and is directly accessible by the elevator. This encourages social interaction between residents on each floor as they have to pass through the common to reach the private. A drying room is also accessible from this space.

By opening the ground plane up on these three towers, the ground plane becomes an extension of the common room and combines existing programs outside with those that happen within. Existing paths continue to exist however they become elements in which to traverse from beneath the new sisters which sit above site. While enhancing and adding onto TJ Hickey park, the new groundplane connection focuses on three key principles: preservation of existing resident behaviours, enabling passive surveillance, and creating clearer connections between new and old areas. After observing interactions residents have with the existing park space, creating availability to not traditionally sit and relax on a bench setting was considered. By raising the groundplane adjacent to the existing tower by 2 metres, the area builds on a common behaviour of sitting on the grass rather than provided benches, facilitated through varying ramps, flowing stairs and undulating grass. Views towards the existing basketball court are enhanced by a flowing stair case on the southern edge of the new landscape intervention, act similar to an amphitheatre.

The landscape intervention extends also to cover part of the carpark, currently used by residents as a meeting space between thresholds, and now further enhanced by continuing the flow of the park further north west. Similarly the new built up level allows residents to circulating around the tower toward the existing community garden to the north, providing more opportunities for egress between green spaces on the site. Allowing a porous groundplane below the additional sister towers naturally allows residents to progress and use the footpaths existing with ease, and further allow the city of Sydney marked bike path to flow despite the presence of higher density. A porous undercroft allows shelter for residents in varying weather conditions which is currently limited on the estate, as well as facilitates new meeting space and new communal interactions to occur. Balconies, on both the existing and new were critical points of connection to the outside, which were seen as key moves in enhancing the conditions already existing.

EXCERPTS FROM PORTFOLIO